SEED Fund / “Creative/Critical/Collaborative” writing retreat

Aio Wira Retreat Centre, Waitakere, New Zealand

13-16 December 2016

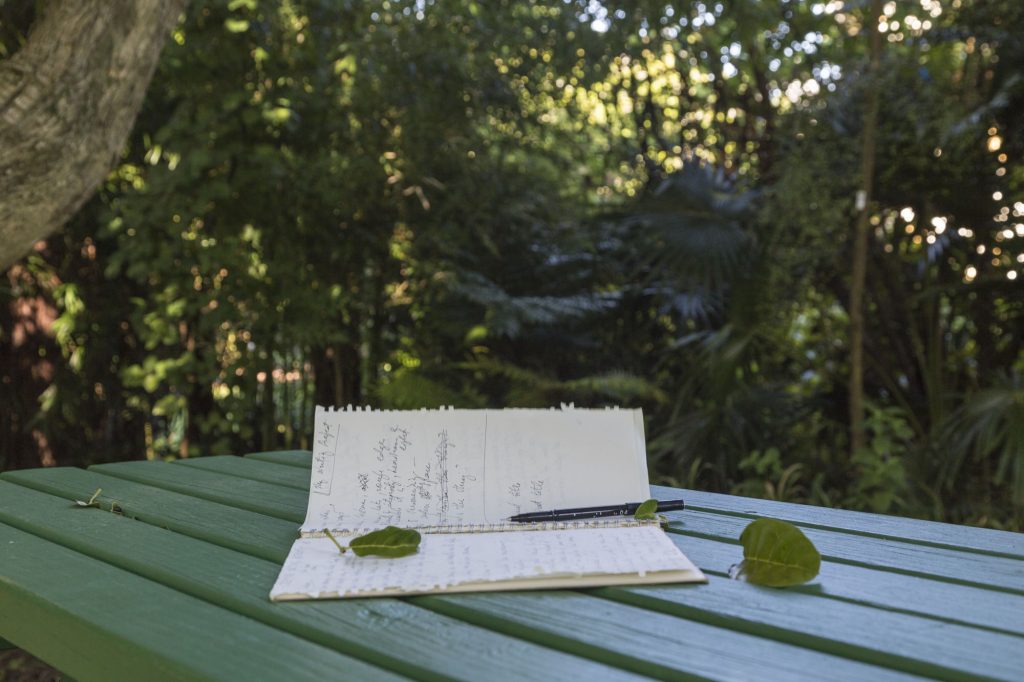

CLeaR’s year of “Writing, writing everywhere” started last December with some early-summer sowing of creative impetus. Our first Creative / Critical / Collaborative writing retreat, which involved a small but diverse group of academics, one professional staff member and one student, transplanted us from the familiar campus setting (noise, email, busy, students, deadlines, can’t!) to a yoga centre in a lush wilderness away from Auckland, filled with native plants and birdsong. Nature cooed and oozed at us from all sides. At night, mosquitoes, mud and moonlight reminded us that were away from home. And, during the day, the blue skies, the delectable home-made food and the hammock in the sun-lit clearing made as feel both happy and guilty about being “away” from work.

The apparent disassociation between pleasure and work in academia has become so huge that, whenever positive aspects (comfort, nourishment, joy) enter workspace, we feel pressured to justify their presence, as also this (name the author) recent blog post on writing retreats suggests. Indeed, why waste university resources on funding something that can be done (should be done?) in the primary work environment – on the campus? Much has already been written about the need for writing retreats (they provide academics with an exclusive time-space for writing, foster a sense of community, encourage collaboration, etc.), so I will not go into much detail about that.

Instead, I want to focus on another, less obvious, value that writing retreats hold. A retreat enables important preconditions for the mental processes that precede, seed and nourish creative and productive writing – for, as we know, writing involves more than merely putting words on paper or screen. A retreat sets up the right mental space from which creativity can emerge.

Having observed over several days how creative writing emerged from versatile artistically, poetically, technically and/or scientifically inclined minds, I concluded that one precondition was interplay between two opposites:

relaxation and tension

boredom and excitement

freedom and constraint

play and work

etc.

Consider, for example, the following scenes of writing that took place during out retreat.

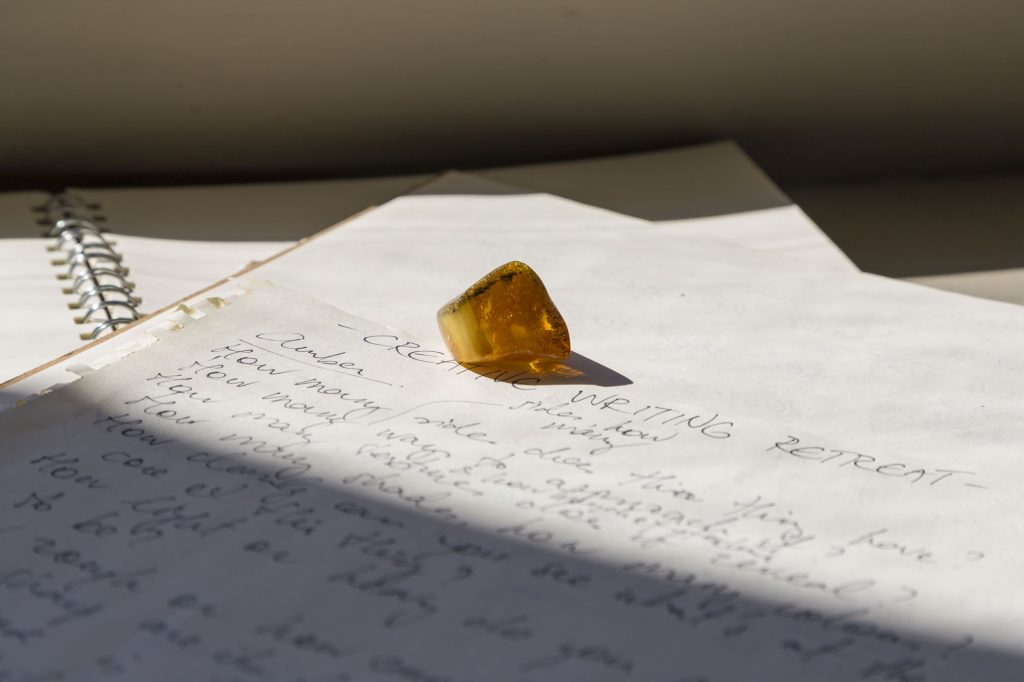

Scene One

Photo credit: Tony Chung

Fifteen academics from various faculties, an administrator, and a postgraduate student are sitting cross-legged or slouching in a circle on the carpeted floor of the yoga room. They are silently writing, trying to describe the ways in which the small object each has placed in front of their eyes represents their research. Their writing is a free outpouring of thought, yet it is also pressured, with mere 15 minutes given by the workshop facilitator to complete the task.

More pressure is applied to the next task – participants now have to choose a number of words from their braindump and create a six-line poem using those (“Is that okay if my poem does not rhyme?” asks someone who has never written poetry before and who later impresses us by his work). Why “force voluntarily” academics to write poetry? When applied to research, metaphor, which is at the heart of poetic form, helps one see their work in a new light and from unexpected angles. It helps one get out of the box of disciplinary thinking, gaining a more holistic understanding that abounds in creativity, vibrancy and interconnectedness of all things.

By the end of the little exercise, everyone has written a few poems – mostly their “first ever”. Those pieces, written by health scientists, engineers, and humanities and social sciences scholars alike, emerged from a pressured play, or from creative freedom combined with helpful constraints, or from the kind of tension one finds in the mixture of pleasure and work.

In other words,

creative productivity = relaxation / boredom / pleasure / play + tension / pressure / rules / work

Scene Two

In the afternoon of the same day, split into small groups and assigned collaborative tasks, we dissolve across the retreat’s outer territory. After a walking-talking mini tour (which helped to get the thinking “going”), my group settles down on the grass by a hammock that hangs at the edge of a small clearing.

This is almost too idyllic: blue skies, warming sun and light breeze, Nature chirping and cuddling everywhere.

We are discussing “sensory writing”, “natural writing” and “happy writing” (is the latter even possible, apart from children’s literature, we ask).

With a satisfied grunt my colleague slides into the hammock; the first hammock experience in her life.

We have changed our topic to the different types of “energies”, pondering whether the writer’s energy indeed translates onto the written page. Lying flat or sitting on the grass, we are idly drafting a miniature essay on “writing energy” to be presented to the others afterwards.

Before we finish, I sneak into the empty hammock, and, for a while, all I see is the deep blue skies above, and a few lonesome clouds making their way across. It feels as if time has stopped, and yet I am present and alert. What an unlikely image of thought-creation; almost obsolete in the present-day world. One’s body so relaxed, yet the mind so active – what a powerful combination.

We know the best ideas often emerge exactly in those moments when we are relaxed yet alert (think of taking a shower, running or gardening). And that condition seems an almost impossible phenomenon to be found on present-day university campuses.

I think initiatives like writing retreats create more than just the so-called “third space”, a space that contains no distractions of one’s home (“first space”) or workplace (“second space”). They enable more than merely a space of “no distraction”. Ideally, they bring together all the above-mentioned preconditions for productive creativity: pleasure, work, relaxation, tension, comfort, awareness of the present moment, nourishment, hunger for creation, and, importantly, a slight dose of quiet, stillness and/or boredom, out of which new ideas can emerge.[1]

Photo credit: Tony Chung

Because writing – working! – leisurely and playfully is often seen as antithetical to productivity, creative-comfortable-critical thinking spaces that encourage such writing are hard to come by in most academic environments. In a sense, then, creation of such spaces and conditions is the main task and the main value of a writing retreat.

Here are some of the “pressured creativity” tasks our facilitator, renowned poet and academic, Selina Tusitala Marsh gave us.

Exercise “The Object”

(courtesy of Selina Tusitala Marsh)

Task 1: pre-writing (helps set up good atmosphere and prepare the soil for writing)

Bring an object that represents your research project “right now”. Don’t show anyone. Place into a lidded basket. People from the group (or two teams) will be asked to match the object to its owner, faciliator to time the exercise for one minute. There is usually lots of laughter. At the end of the fun selections, people own their object and get to tell the group why they chose that object now.

Task 2: free writing (helps get ideas down on paper and engage with free association)

Writing: Time a 15 minute free writing session (pen doesn’t stop moving). Write freely, openly, experimentally about your object. Do not edit as you go along. Why does it represent your research? What aspects about the object represent the challenges/beauty/worthiness/difficulties about your research? What new things might it tell you about your research? You should have at least a page of writing…

Task 3: poetry-writing (helps consolidate links between metaphor and research)

Revisit the writing from above exercise. Reading quickly and instinctively, circle six* words that energise or excite you from your piece of writing. Write each word down the side of your page, one word per line. Write a six-lined poem using a different word for each line. The word can appear anywhere in the line. Give your poem a title. Try the name of the object as a title. Try your research project as a title. See which one fits best with your poem. Suggest and evoke rather than ‘tell’. Read out your poem to the group. Spend 10 minutes editing your piece thinking about injecting concrete details, as led by your object. Think about colour, texture, purpose, composition. Is the line order the most effective? Focus on your strongest line and think about shaping the poem around that particular description/event/scene. Read out the revised poem to your partner.

* try the exercise with 8 words, then 12 words.

[1] As the legendary Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky has said, one needs from time to time to find oneself in comfortable solitude, quiet and bored, in order to think of something new.